Suicide is regarded across the country and world as a serious public health issue. In the United States, suicide is the second leading cause of death among people aged 15 to 24. A CDC study in 2019 found that 18.8% of high school students surveyed reported having seriously considered attempting suicide. Importantly, too, it can be prevented.

Given the prevalence of this tragedy, it’s possible that your child or teenager will be exposed to suicide — either through their own personal community, at school, or among their family. They may be grieving a loss and want someone to talk to. They may be supporting a friend through depression, or they may themselves be dealing with their own mental health struggles. It’s also possible that they may be exposed to suicide through the media, including television or the news.

Talking about suicide, for many reasons, is extremely and understandably difficult. For this reason, it is a conversation that is often avoided. However, opening space for compassionate discussions about mental health and suicide is extremely beneficial and can even help prevent it from happening.

Consider their age and the context

A discussion about suicide does not have to be instigated by a parent completely out of the blue. For younger children, it should be a conversation prompted by an event, questions, or behavioral changes in your own child (e.g., incorporating themes of death or suicide into play). Do not feel you need to push the conversation if your child is not directly asking. Though, when it is prompted, then it is important to have an open and honest conversation about the topic.

If they do have questions, you may allow your child to lead the conversation, and depending on their age, slowly add details without overwhelming them. For younger children, you should focus on general descriptions and hold back from giving many details, especially if not directly asked.

But as children grow older, they may have more questions for you, or they may have developed their own understanding of what suicide is. Even though you may feel you need to protect your children from this difficult topic, there is no need to lie to them. Providing opportunities for open conversations will lessen the stigma around mental health and increase the likelihood that your child will come to you to talk about other sensitive topics in the future.

For high school aged teenagers, the topic of mental health, including depression, anxiety, and suicide, will be more common – among their own friends and communities, as well as across media. In these instances, if the topic is prompted, you may want to gauge how much your teenager already knows, and have an open conversation with them – it may be a major sense of reassurance or relief to know their parent can handle an open, compassionate conversation about the topic.

If someone has died of suicide

If a family member, loved one or community member has died by suicide, be open with your child about the cause of death. If your child is very young, keep the message short and to the point. You can say, for example, “This person has died. It’s very sad and they loved you so much.”

For older children, do not feel the need to shield them from the truth. Instead, based on their age and levels of understanding, you can alter how much detail is given, and let your child steer the conversation with questions.

Everyone grieves differently. Grieving a death by suicide is complex and comes with additional layers of difficulty, emotions, trauma, and confusion. If your child is grieving, support, listen to, and comfort them. Give them time and space to ask questions and talk through their feelings. Remember that you can also be supportive while telling them – and yourself – that you don’t have all the answers.

Be kind and gentle to yourself – supporting a child through grief is a difficult thing, and you are only able to do the best that you can. Turn to other forms of support too, which can include other family members, friends, community members, and trained professionals.

Dispelling myths about suicide

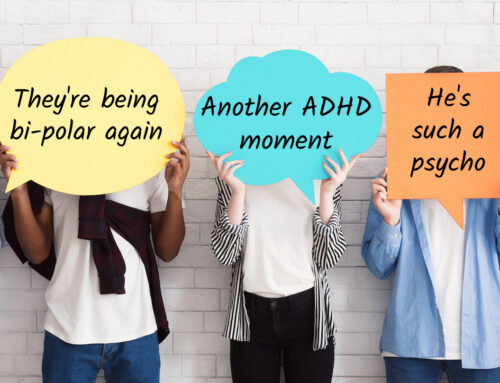

Suicide and suicidal ideation are unfortunately tied to strong stigma in society, as well as many harmful myths and misunderstandings associated to it. These myths may make the grieving process more difficult. For those who have experienced suicidal ideation, myths and stigma can prevent them from doing the important work of seeking help for themselves.

As a guardian, you can help play a role in decreasing the stigma of suicide. Remind your child that suicide or depression is not a character flaw of a person. It also certainly should not be seen as selfish or weak. On the other hand, don’t contribute to any glorification of suicide, as some media including television and movies do.

If your child is grieving, normalize then dispel any notions of blame or guilt. You can also help your grieving child accept that some questions may never be answered. Remind them that nothing is their fault.

Do not let this stigma and these myths stop you or your child from speaking up about suicide. Talking about suicide will not suddenly plant the idea in your child’s head. Breaking the silence on the topic may help your child reframe the issue, talk through their thoughts, and signal that you as a parent value positive mental health and care about your child, among other benefits. This conversation can also jumpstart finding more resources and support for your child when it’s necessary.

Check in with your child

We’ve covered some advice for if your child is exposed to or grieving a death by suicide, but what if your child is the one at risk?

Some children and teenagers will give signs, even explicit ones, that they have thought about suicide — and if they do, it’s important for you to tune in. Others may never come directly to their parents, or anyone at all.

If your child is experiencing behavioral changes — including with their sleep, social habits, isolation, or mood swings — it’s possible they may be experiencing issues with their mental health. They may express feelings of being trapped, hopeless, intense pain or sadness, or finding it difficult to find a reason to live. If they do, it is essential to tune in and act as a support for them. Other large warning signs can include things like taking dangerous risks, researching ways to die, saying goodbye.

If you have some worries about your child, you may want to begin by asking broad questions about their mental wellbeing, starting with broad questions like, “How have you been, really?” and “You haven’t been yourself lately. What’s been on your mind?” You can work towards more pointed questions, including “When did you last feel very sad, hopeless or lonely?” or “What has been motivating you lately?”

Even before you begin seeing any signs, remind your child that you love them unconditionally and that you are always open to hearing about the problems they are dealing with, including those related to their mental health.

Make it very clear that if they are in any way suffering, they should seek help — and not feel ashamed or nervous about asking for it. Ensure that you are making yourself available as a compassionate source of support.

In taking early steps like these, you can create space for honest and trusting dialogue with your child about mental health, so they feel they can come to their parents and guardians when they need to talk or ask for more help.

If your child is having suicidal thoughts

If your child is having suicidal thoughts or begins verbalizing ideas related to suicide, including feeling hopeless or wanting to die — tune in and take it seriously. Them voicing that “nothing matters”, they don’t “care anymore”, or that things “would be better off without them” are worrying signs that should be taken with a lot of weight and importance.

These feelings may be tied to mental health issues. These may also be exacerbated by both external and internal conditions including loss, bullying, isolation, anxiety about a change and other risk factors.

Do not minimize the feelings; some things that might seem helpful, for example saying “But you have such a wonderful life” or “You can’t possibly mean that” can delegitimize their feelings. Instead, listen with compassion, acknowledgment, and validation. For example, a more helpful thing to say would be “What you’re describing sounds really difficult. Let’s talk more about it.”

It may also be tempting to jump to an extreme solution, like, “I’m taking you to the hospital” or “You need to go to inpatient therapy.” However, the message the child might receive is that there is something wrong with them that needs to be fixed and their parents are feeling just as helpless. Instead, try identifying the underling feeling (e.g., anxiety, sadness, fear, helplessness), validate that emotion, and reassure them that you are there to help them feel better and keep them safe.

It is normal and okay for you to tell your child that you do not have all the answers. However, if they are displaying signs of suicidal ideation, it’s important that you reach out to professionals trained to handle this situation. If you are unsure if your child is safe, call the crisis hotline (#988) and schedule a therapy appointment for your child. The crisis hotline can work with you to keep your child safe until they are able to be assessed by a trained professional.

_____________

If you or your child is experiencing a mental health crisis, seek help immediately. Call 988 to reach the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline or text HOME to 741741 to reach a counselor.

At Georgetown Psychology, we offer therapy for people who are experiencing mental health problems, including depression.